The Post-Literate Society?

An Annotated Critique

I’ve responded to James Marriott’s intriguing new essay on the impact of technology and media on our post-industrial society below. In doing so, I’ve adopted a slightly different format than usual, but, as ever, I do hope readers enjoy it and find some value in how I’ve approach the task at hand. You can read the original article here (link).

The Age of Print

James starts his essay in the 18th Century, outlining the impact of the ‘reading revolution’. As he rightfully notes, though there was a literate society in the West before the 1700s, it was not a mass population phenomenon.

The oral tradition of passing on information and knowledge by word-of-mouth was much more pronounced. Here, I thought it would be important to bring in some historical context.

Though printing presses had emerged in the 15th Century, the industry was heavily suppressed by censorial legislation and taxation. In England, for example, prospective texts would have to be submitted to the Stationers’ Company for publication.

It wasn’t until after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when John Locke and the early Whigs were able to defeat the Licencing Act, stop pre-publication censorship and start to undermine the monopoly of Stationers’ Company.

Crucially, printing presses were also then able to expand beyond Cambridge, Oxford and London. This liberalisation would eventually spread across the British Empire and it would eventually help foster the American Revolution (link).

Scotland had a slightly different story, one which was intertwined with the Kingdom’s religious sensibilities. John Knox and the Presbyterian movement thought it was increasingly important that God’s people were closer to their creator.

As such, they were encouraged to read the bible in their native language, rather than Latin. Literacy therefore became a core tenant of the Scottish Reformation.

The First Book of Discipline (1560) outlined a plan to have a school in every parish across Scotland. Though this bold ambition was never met in the 16th Century, by the end of the 17th Century the Scottish lowlands had high literacy levels and it is estimated that more than a third of the national population knew how to read (link).

The role of religion in the ‘reading revolution’ is often skirted over in our secular age, but it was clearly important and perhaps even foundational, as was the case in Scotland and Sweden.

Moving away from the spiritual realms and towards the temporal, technology, advancements in printing and transport networks also had profound impacts on the literary society.

The Turnpike roads of England increasingly made it easier to transport early newspapers and books across the nation (more about their history here), while printing presses became more efficient and their operators became increasingly skilled.

The early 17th Century would also see the business model behind printing change, moving from political patronage towards a system where consumers would ultimately fund this insurgent industry. The early Industrial Revolution and increased urbanisation also helped the ‘literary society’ grow.

Here’s what James writes:

It was one of the most important revolutions in modern history — and yet no blood was spilled, no bombs were thrown and no monarch was beheaded.

Perhaps no great social transformation has ever been carried out so quietly. This one took place in armchairs, in libraries, in coffee houses and in clubs.

What happened was this: in the middle of the eighteenth century huge numbers of ordinary people began to read.

For the first couple of centuries after the invention of the printing press, reading remained largely an elite pursuit. But by the beginning of the 1700s, the expansion of education and an explosion of cheap books began to diffuse reading rapidly down through the middle classes and even into the lower ranks of society. People alive at the time understood that something momentous was going on. Suddenly it seemed that everyone was reading everywhere: men, women, children, the rich, the poor. Reading began to be described as a “fever”, an “epidemic”, a “craze”, a “madness”. As the historian Tim Blanning writes, “conservatives were appalled and progressives were delighted, that it was a habit that knew no social boundaries.”

This transformation is sometimes known as the “reading revolution”. It was an unprecedented democratisation of information; the greatest transfer of knowledge into the hands of ordinary men and women in history.

In Britain only 6,000 books were published in the first decade of the eighteenth century; in the last decade of the same century the number of new titles was in excess of 56,000. More than a million new publications appeared in German over the course of the 1700s. The historian Simon Schama has gone so far as to write that “literacy rates in eighteenth century France were much higher than in the late twentieth century United States”.

Where readers had once read “intensively”, spending their lives reading and re-reading two or three books, the reading revolution popularised a new kind of “extensive” reading. People read everything they could get their hands on: newspapers, journals, history, philosophy, science, theology and literature. Books, pamphlets and periodicals poured off the presses.

…

Even more importantly print changed how people thought.

The world of print is orderly, logical and rational. In books, knowledge is classified, comprehended, connected and put in its place. Books make arguments, propose theses, develop ideas. “To engage with the written word”, the media theorist Neil Postman wrote, “means to follow a line of thought, which requires considerable powers of classifying, inference-making and reasoning.”

As Postman pointed out, it is no accident, that the growth of print culture in the eighteenth century was associated with the growing prestige of reason, hostility to superstition, the birth of capitalism, and the rapid development of science. Other historians have linked the eighteenth century explosion of literacy to the Enlightenment, the birth of human rights, the arrival of democracy and even the beginnings of the industrial revolution.

The world as we know it was forged in the reading revolution.

The Counter Revolution

James then jumps ahead three hundred years to the present day, arguing that literacy is now in decline. He cites a series of reputable studies and paints the the chief villain in this story as the smartphone:

What happened was the smartphone, which was widely adopted in developed countries in the mid-2010s. Those years will be remembered as a watershed in human history. Never before has there been a technology like the smartphone.

Where previous entertainment technologies like cinema or television were intended to capture their audience’s attention for a period, the smartphone demands your entire life. Phones are designed to be hyper-addictive, hooking users on a diet of pointless notifications, inane short-form videos and social media rage bait.

Though I may agree with James’ overall sentiments, I think it’s worth pointing out that the rise of broadband internet and social media platforms, especially ones which adopted news-feed-style structures, have been just as impactful.

Of course, those apps would be transferred onto smartphones, with short-form video and picture platforms, including Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok, gaining great popularity at the end of the 2010s.

Here you can see an important distinction between the hardware and software, and this is somewhere I depart from James’ thinking.

Smartphones, in and on themselves, may be increasingly designed to be a one-stop-shop for information, communication and entertainment, but it’s the apps which have prioritised gamification algorithms in a bid to boost engagement.

That’s why certain ‘dumbphones’, which still have 5G, Bluetooth and Wifi connectivity, limit the number of apps a user can download. They are increasingly popular with parents (link).

James continues:

The average person now spends seven hours a day staring at a screen. For Gen Z the figure is nine hours. A recent article in The Times found that on average modern students are destined to spend 25 years of their waking lives scrolling on screens.

If the reading revolution represented the greatest transfer of knowledge to ordinary men and women in history, the screen revolution represents the greatest theft of knowledge from ordinary people in history.

Our universities are at the front line of this crisis. They are now teaching their first truly “post-literate” cohorts of students, who have grown up almost entirely in the world of short-form video, computer games, addictive algorithms (and, increasingly, AI).

Because ubiquitous mobile internet has destroyed these students’ attention spans and restricted the growth of their vocabularies, the rich and detailed knowledge stored in books is becoming inaccessible to many of them. A study of English literature students at American universities found that they were unable to understand the first paragraph of Charles Dickens’s novel Bleak House — a book that was once regularly read by children.

If we are talking about “ordinary men and women”, as James evokes above, I wouldn’t have it that “ordinary men and women” attend Oxbridge or are English literature students at elite America universities, and therein lies another contestable point of his wider argument.

Tastes simply change and that’s especially true of popular literature (personally, I prefer more utilitarian wordsmiths like Orwell, who James cites in his references, rather than a writer who overdoes the flowery language and impenetrable paragraphs).

And for the past 50 years, TV and cinema have supplanted literature as the primary form of entertainment, creating a cultural zeitgeist of its own — one in which the book industry is downstream of.

The Web 2.0 platforms have merely inherited TV and cinema’s mantle as the culture-setters. Why else would publishers print ‘As Seen on Netflix’ on sleeve covers or seek to engage with TikTok influencers who have built massive followings recommending books (link)?

I would redefine the problem for James. It’s not that Gen-Z students can’t literally read the course materials, it’s that they digest it in an entirely different way and the texts themselves may have no cultural relevance to them.

This may be a problem which stems from the student, but it’s also a major issue for the Academy. As the world moves quickly on, how relevant are English literature lectures and are they being taught in an effective and modern manner?

He goes on:

The tradition of learning is like a precious golden thread of knowledge running through human history linking reader to reader through time. It last snapped during the collapse of the Western Roman Empire as the barbarian tides beat against the frontier, cities shrank and libraries burned or decayed. As the world of Rome’s educated elite fell apart, many writers and works of literature passed out of human memory — either to be lost forever or to be rediscovered hundreds of years later in the Renaissance.

That golden thread is breaking for the second time.

These statements feel slightly overdone, especially since we’re literally still discovering what the ancients read (you can read more about these efforts in my article on the Oxyrhynchus Papyri here).

I would argue that the fabled “golden thread” is being defined, rather than being undermined, as has been the case for over 300 years.

I can tell you with great confidence that fisherman today no longer read Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler, a colourful guide first published in 1653.

An Intellectual Tragedy

James expands his argument that we’re in a cognitive freefall by brining in more reporting and more studies. John Burn-Murodch’s FT article (link) on declining global PISA scores, a well-recognised measurement of educational attainment, is cited heavily.

Most intriguing — and alarming — is the case of IQ, which rose consistently throughout the twentieth century (the so-called “Flynn effect”) but which now seems to have begun to fall. The result is not only the loss of information and intelligence, but a tragic impoverishing of the human experience.

There is no doubt that these metrics are worrying. However, there is little to no acknowledgement of another Murdoch. That is Rupert Murdoch and his burgeoning book business. Here’s what Bloomberg said of the News Corp division in May 2024 (link):

News Corp., Rupert Murdoch’s publishing company, is finding its footing as a separate business, with stronger profits from book publishing helping combat the downturn in the ad market.

Profit, excluding some items, was 11 cents a share in the fiscal third quarter, surpassing the 3 cents analysts estimated on average, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The company reported $2.08 billion in revenue for the period, which ended March 31. Analysts projected $2.06 billion. Like many publishers, Chief Executive Officer Robert Thomson is working to transform the company’s print properties into a digital business as well as expand into markets around the globe.

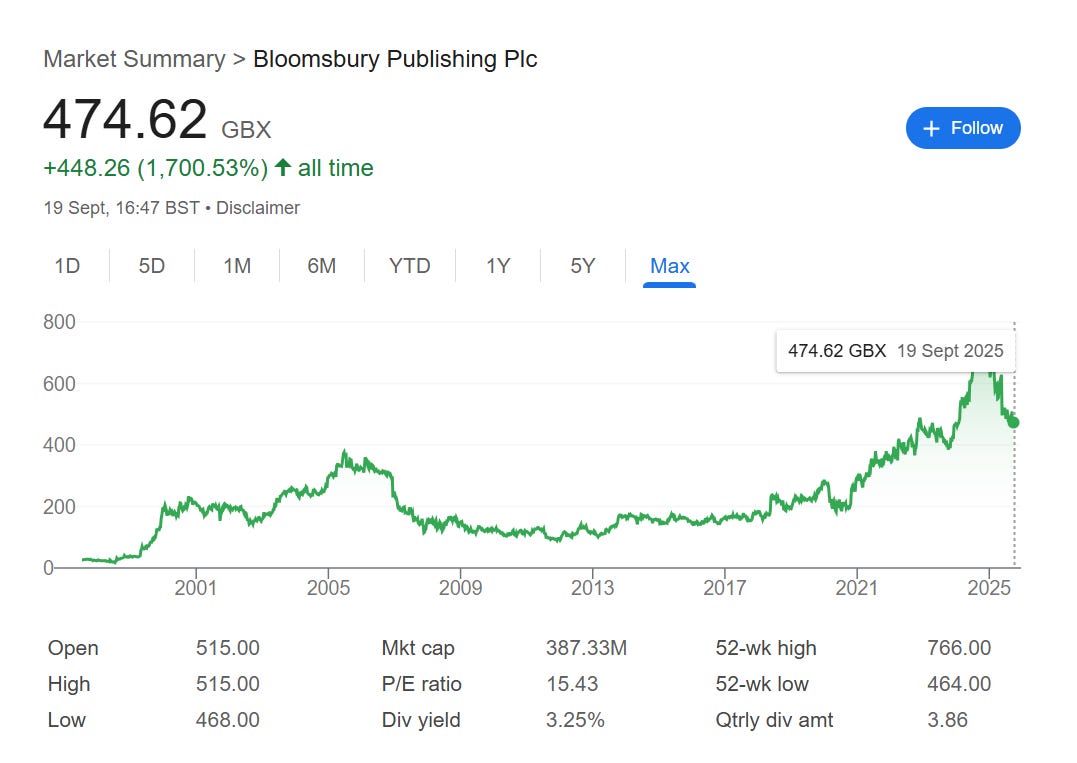

This doesn’t sound like an industry which is in decline to me. More evidence comes from Bloomsbury, the publisher behind the Harry Potter franchise. The company’s share price has slipped since its all-time high in 2024, but it’s current performance of around £4.70 per share is still very high compared to most of its history as a publicly-listed business.

These facts seem to have alluded James. He goes on:

The epidemic of anxiety, depression and purposeless afflicting young people in the twenty-first century is often linked to the isolation and negative social comparison fostered by smartphones.

It is also a direct product of the pointlessness, fragmentation and triviality of the culture of the screen which is wholly unequipped to speak to the deep human needs for curiosity, narrative, deep attention and artistic fulfilment.

I like to think we’re turning a corner and the benefits, rather than just the downsides, of smartphone and Web 2.0 technology is often overlooked for dramatic effect. I’ve previously written about the positive impact of hiking apps on the offline world (link) and I also note that there are a range of language learning, mental health and wellbeing apps available today.

Having said that, I readily acknowledge that countries like Australia are banning social media platforms for teenagers and there is now a growing movement to police this technology more closely.

As a sports fan, avid weightlifter and former rugby player, I would be keen for policymakers to push for more offline interventions, including more physical education classes. Here’s what the Centre of Social Justice’s recent ‘Lost Boys’ report says on the matter (link):

Our qualitative research, especially in Alternative Provisions outside mainstream education, highlighted the importance of exercise and physical activity for young boys within the education system. A common theme from youth workers was about how Physical Education (P.E) or outdoor games was one a boy’s best experience of an otherwise negative time in school.

One conversation with some boys from a LA that ranks in the top ten IDACI scores in the country went as follows: We asked what the best thing about school was. The three immediate responses were ‘nothing’, ‘P.E’ and ‘substitute teachers’.

This not only exemplifies the great dissatisfaction of some of the boys and their potential antagonism with their regular teachers (one boy even cited how he felt that teachers at his previous schools seemed to constantly pick on him when he was struggling with English and Maths at primary school) but also how fundamental sport is to engaging young boys.

Healthy body, healthy mind; healthy mind, healthy body.

World Without Mind

James goes on to issue another warning. That the decline he’s outlined could undermine the roots of Western civilisation itself:

This draining away of culture, critical thinking and intelligence represents a tragic loss of human potential and human flourishing. It is also one of the major challenges facing modern societies. Our vast, interconnected, tolerant and technologically advanced civilisation is founded on the complex, rational kinds of thinking fostered by literacy.

As Walter Ong writes in his book Orality and Literacy, certain kinds of complex and logical thinking simply cannot be achieved without reading and writing. It is virtually impossible to develop a detailed and logical argument in spontaneous speech — you would get lost, lose your thread, contradict yourself, and confuse your audience trying to re-phrase ineptly expressed points.

I generally agree that true critical thinking and intellectual honesty is now a rarity. Book reading would certainty help, but it needn’t be limited to literature.

Many academic journals are now easily accessible online and the amount of fiction and non-fiction information on the web is vast. Equally, when James talks of philosophy, he should be aware that analytic philosophy has taken a narrow turn.

It is increasingly interested in meta arguments, rather than broad metaphysical surveys of the world and its inhabitants. That means analytic philosophy is simply not taking on the big questions.

Perhaps Nozick vs Rawls (in the 1970s) was one of the last meaningful debates in the Anglo-American tradition. If you’re interested in rights, justice and the role of the state, it is worth looking into.

The End of Creativity

Here, James successfully argues that future students will be increasingly reliant on their teachers and other figures of authority to supply them with information.

Because they won’t be able to interpret source texts themselves, students will have to build upon or manipulate aggregations or summaries. It’s a Jean Baudrillard-esque situation (link).

Or for those not familiar with the Frenchman’s philosophy, it would be like three-chord punk rockers ripping off each other — there might be some musical gems, but the overall output would be inherently limited:

Modern students who are unable to read are once more reliant on the authority of their teachers and are less capable of racing ahead, innovating and questioning orthodoxies. These students are just one symptom of the stagnant culture of the screen age which is characterised by simplicity, repetitiveness and shallowness. Its symptoms are observable all around us.

Harking back to our 16th Century historical context at the start of this critique, this is exactly what the aforementioned Knox and Co. were fighting against some 450 years ago.

The Death of Democracy

Much like our Reformation example, James outlines his own political consequences for the ‘illiterate society’, which, initially, look sound:

In Amusing Ourselves to Death Neil Postman argues that democracy and print are virtually inseparable. An effective democracy pre-supposes a reasonably informed and somewhat critical citizenry capable of understanding and debating the issues of the day in detail and at length.

Democracy draws immeasurable strength from print — the old dying world of books, newspapers and magazines — with its tendency to foster deep knowledge, logical argument, critical thought, objectivity and dispassionate engagement. In this environment, ordinary people have the tools to understand their rulers, to criticise them and, perhaps, to change them.

He adds:

Politics in the age of short-form video favours heightened emotion, ignorance and unevidenced assertions. Such circumstances are highly propitious for charismatic charlatans. Inevitably, parties and politicians hostile to democracy are flourishing in the post-literate world. TikTok usage correlates with increased vote share for populist parties and the far right.

To me, this is putting the egg before the chicken. TikTok has certainly had an impact on the social media ecosystem — YouTube had to respond by launching its own short-form video platform, as just one example — but Facebook, Instagram and YouTube are still the dominant players in the space. Here’s OfCom’s latest media consumption survey to prove that point (link).

Perhaps more ‘populist parties’, as James would potentially describe them, are also “flourishing” because voters feel unheard when it comes to their top issues (immigration, the economy and healthcare), inflation is still high across the Western world and taxes are increasing to meet high government debt and spending levels (link).

Though short-form video is helping insurgent parties get these messages across, you can’t escape this macro-economic and political reality.

The Moronic Inferno

And all of this leads to James’ conclusion:

The big tech companies like to see themselves as invested in spreading knowledge and curiosity. In fact in order to survive they must promote stupidity.

The tech oligarchs have just as much of a stake in the ignorance of the population as the most reactionary feudal autocrat. Dumb rage and partisan thinking keep us glued to our phones.

And where the old European monarchies had to (often ineptly) try to censor dangerously critical material, the big tech companies ensure our ignorance much more effectively by flooding our culture with rage, distraction and irrelevance.

These companies are actively working to destroy human enlightenment and usher in a new dark age.

The screen revolution will shape our politics as profoundly as the reading revolution of the eighteenth century.

Because of the Shareholder Value Movement of the 1980s which is still incredibly influential today (link), the listed Big Tech companies are most interested in pleasing their investors.

How do they do this? If they’re a social media company, Wall Street is fixated on one particular metric: average revenue per user or ARPU. If your company has a high ARPU compared to its rivals and peers, it should be doing very well, so long as that is also the case for the business’ revenue and profit lines.

Social media companies have been able to increase ARPU rates by making their platforms more engaging. This has worked in the short-term, but another way to generate a high ARPU score is to create a service which has deep value for users.

This would allow social media companies to charge a premium for access to such an offering. If the service is popular, the ARPU rate should increase.

Since you can only do so much with short-form video, this may be a route the social media companies pursue in the future. We are already seeing a reembrace of long-form, under-produced content on YouTube (link).

If this trend continues, the tech companies will have to embrace it to survive. This is why I’m much more optimistic about the future than James is. So, are we in a post-literate society? Not quite. Will we get there? You’ll have to ask AI.

The Political Press Box

Find my latest long-form audio interviews of political communicators here. Please like, subscribe and listen.

📧 Contact

For high-praise, tips or gripes, please contact the editor at iansilvera@gmail.com or via BlueSky (link). Follow on LinkedIn here.

219 can be found here

218 can be found here

217 can be found here

216 can be found here

215 can be found here

214 can be found here