How a Working Class Hero Saved British Boxing TV

When his sport faced obscurity, Ricky 'The Hitman' Hatton emerged as an exciting knock-out artist with serious PPV power

The boxing gods, they give and they take. Just hours after Terence Crawford ascended to legendary status on Netflix by overcoming Mexico’s Canelo Álvarez in a brutal 12-round bout, the death of Ricky Hatton was announced (link). It was a body blow for all boxing fans, but it was especially sore for us Brits.

A working-class lad from the outskirts of Manchester, Hatton rose to fame during the fallow years of modern British boxing, well before Anthony Joshua and Eddie Hearn’s Matchroom were in their pomp.

Back in the 2000s, before the rise of the heavyweights, the main stars were smaller, faster and arguably more entertaining. But the pay-per-view (PPV) numbers were lower.

It was evidently clear that the last golden era of British boxing, starring Frank Bruno, Lennox Lewis, Chris Eubank and Nigel Benn, had become history.

There were no ‘big fights’ anymore, the type of match-ups that packed the pubs up and down the nation. That was until Hatton’s star started to shine.

A fried food loving, beer guzzling, no-nonsense Mancunian, Hatton’s down-to-earth personality resonated with the public and so did his boxing style.

The light-welterweight would often sit in the pocket, absorb danger and then dispatch his opponents with crushing body blows (link). Hatton’s penchant for knockouts would earn him the ‘Hitman’ moniker.

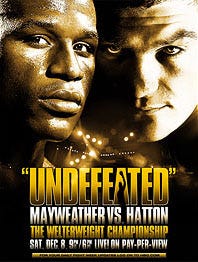

The world titles, TV appearances and ‘best of’ DVDs would follow, but Hatton’s legend would really be formed after he secured a 43-0 record. He put his undefeated status on the line against Floyd Mayweather Jr. in the winter of 2007.

The clash made for fabulous theatre. Despite enduring a tough childhood in Michigan, Mayweather Jr. had built a reputation of a genius villain amongst fight fans. He was flamboyant, cocky and boxed out of the 'Philly shell', a defensive but highly negative technique (link).

Hatton was the exact opposite of ‘Pretty Boy’ Floyd, something HBO, Sky Sports and Oscar De La Hoya’s Golden Boy Promotions were keen to make the most of when the pair went on a pre-fight media tour to Los Angeles, New York and Manchester.

Floyd would literally flash the clash, come to press conferences blinged out and try, in vain, to wind-up his opponent (link). In contrast, Hatton thanked the fans, acknowledged the sacrifices of his family and turned out fully suited and booted.

It was all great fun, made even more entertaining by the United States vs. Great Britain undercurrents. When Mayweather travelled to a rain-sodden England, bravely wearing a United strip (Hatton supported Manchester City, their sworn rivals), he was greeted by the trumpets, drums and chants of the Hatton faithful.

The old football songbook was pulled out, with renditions of ‘Rule Britannia’, ‘God Save The Queen’, ‘Who Are Ya?’ and the now iconic ‘One Ricky Hatton’ to the tune of ‘Winter Wonderland’ (link).

The fanfare made it all the way into the MGM Grand in Vegas and outside of it on 8 December 2007. More than 30,000 travelled from Britain to support the Hitman, but only a fraction of fans secured a spot in the small 17,000-seat arena. The media dubbed it the ‘Hatton Invasion’ (link).

Though they were outnumbered, the Brits were near the end of their boxing pilgrimage and they decided to put on a show. Brad Pitt was booed, Tyrese Gibson, of The Fast & The Furious and Transformers fame, was mocked and his rendition of the ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ was drowned out (link).

In contrast, Tom Jones was cheered, the British national anthem was enthusiastically sung (at least ten times) and the Hatton chants rang out. That was until the middle of the 10th round when Mayweather knocked his rival down twice with a left hook (link), ending the fight.

Hatton had been outclassed and outboxed, losing for the first time in his professional career. For his part, Mayweather would retain the prestigious WBC and Ring Magazine welterweight titles and go on to beat the likes of Canelo Álvarez, Miguel Cotto and Manny Pacquiao.

Hatton, meanwhile, would end his career with an impressive 45–3 record, with a notable loss to Pacquiao in 2009. He would make various TV appearances, oversee his own promotion company and become a boxing trainer.

Contemporaries of Hatton’s, including Nottingham’s Carl Froch and Wales’ Joe Calzaghe, benefited from the eye-balls he drew to the sport (Mayweather vs. Hatton did 1.15m PPV buys in the UK alone — at 4am in the morning) and British boxing fans will be forever grateful for the memories he gave us.

Even when UFC star Conor McGregor took on Mayweather in 2017, there were deep similarities between the passionate Irish fandom and the Hatton faithful a decade before, such is the Hitman’s legacy.

But perhaps Hatton’s most important intervention was to stop his own son, Campbell, from boxing when he fell out of love with what has to be one of the world’s toughest jobs (link). He was by no means perfect, but he was our Ricky.

UK boxing PPV records:

2018: Joshua vs Parker, 1.83m

2017: Joshua vs Klitschko, 1.63m

2019: Ruiz vs Joshua 2, 1.57m

2017: Haye vs Bellew, 1.53m

2018: Joshua vs Povetkin, 1.25m

2011: Klitschko vs Haye, 1.17m

2007: Mayweather vs Hatton, 1.15m

2017: Mayweather vs McGregor, 1m

2015: Mayweather vs Pacquiao, 942k

2009: Pacquiao vs Hatton, 900k

The Political Press Box

Find my latest long-form audio interviews of political communicators here. Please like, subscribe and listen.

📧 Contact

For high-praise, tips or gripes, please contact the editor at iansilvera@gmail.com or via BlueSky (link). Follow on LinkedIn here.

218 can be found here

217 can be found here

216 can be found here

215 can be found here

214 can be found here

213 can be found here