Oppenheimer, Atomic Bill and the Explosive Birth of Science Journalism

Future News 157: The mad story of a patriot, propagandist and scoop-hunter

IT WAS A FAR CRY FROM A PICKLE BARRELL. William L. Laurence had landed in Tennessee on the cusp of securing the story of a lifetime. Thanks to his perseverance and influential employer, The New York Times, he would soon win another Pulitzer Prize and forever be known as ‘Atomic Bill’.

But first he had to grab a ride from Nashville to a place most Americans would never have heard of at the time, Oak Ridge.

The town, around a 20-minute drive from Knoxville, was attractive to the US Army Corps of Engineers for several reasons. It was tucked away in a discreet location in the middle of the US Republic with a low population, it already had a demolition range and it was far, far away from the Canadian and Mexican borders.

But for a large part the site was selected because of its proximity to the Clinch River, a 300-mile waterway which still flows through the Great Appalachian Valley.

Oak Ridge could also be serviced by two railroads, it was easily accessed by road and its mild climate meant outdoor work would be possible throughout most of the year.

After a bureaucratic delay, The Manhattan Engineers snapped up the site in 1942. The demolition range was turned into the Clinton Engineer Works at the start of 1943, 1,000 families (mostly farmers and rural workers) were moved from the land and Oak Ridge would officially become a military district under federal control that summer.

This decision and the government’s rapid land appropriation programme rustled the feathers of the then Governor of Tennessee, Prentice Cooper, who angrily tore up President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s public proclamation. Cooper, who only learned about the project in July 1943, would have to put his honour aside and let ‘Enormous’, as Soviet spies dubbed it, take over.

Thanks to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and its main sites, including ‘X-10’, the codename for the site’s main reactor, and the ‘K-25’ and ‘Y-12’ uranium enrichment plants, the town’s population would swell from around 800 to 90,000 people. It was no easy feat when materials and people were in short-demand.

The University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory took a leading role in managing the site. In the winter of 1942, and under the direction of Enrico Fermi, a team of the university’s scientists had produced the first nuclear chain reaction at Chicago Pile-1, the world’s first nuclear reactor.

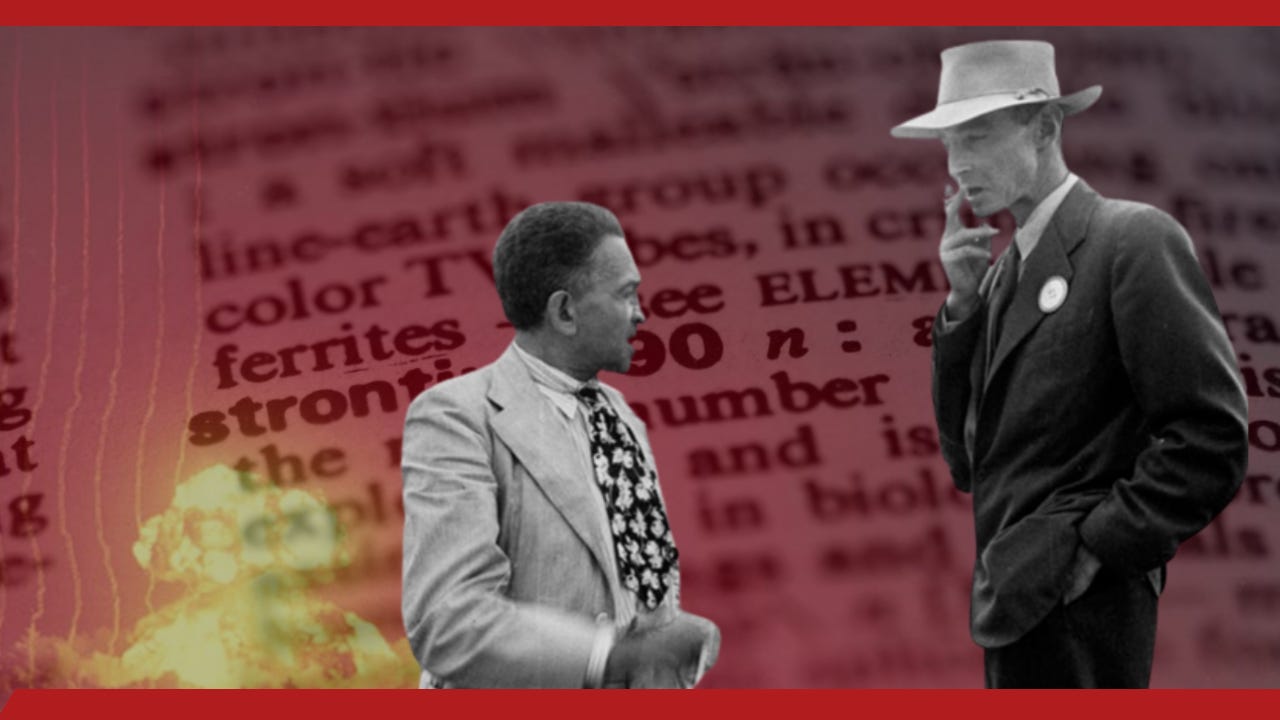

Though it was a great achievement scored in the middle of the war, the US Army’s man-of-action Major General Leslie Groves and The University of California’s J. Robert Oppenheimer would ultimately oversee the Manhattan Project.

The duo was an unlikely one. Groves was initially not meant to lead the project, instead letting Colonel James C. Marshall run the show. That was until an intervention from Vannevar Bush, the overseer of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, who reported directly to Roosevelt.

Bush wanted progress so Groves, with his exceptional project management skills, including helping build The Pentagon, was drafted in.

In contrast, Oppenheimer, with no Nobel Prize, no mass administrative history, a communist wife and only a recent interest in the weaponisation of nuclear physics (as of 1941), would have seemed an odd choice for the job to an outsider.

But Oppenheimer proved to be a skilled convener of some of the West’s greatest minds and alongside Groves he would help coordinate Oak Ridge’s efforts with that of another production site, the Hanford Engineer Works, which was located in Boston County, Washington.

The production sites would feed into ‘Project Y’, The Laboratory at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where Oppenheimer and his warrior scientists (from Princeton to Berkeley) were on a top secret mission to turn experimental physics into a terrifying reality and deliver the world’s first working atomic bomb for the United States.

A Long Way From Lithuanian

Leib Wolf Siew escaped the Russian Empire thanks to his mother, who helped smuggle him from modern-day Lithuania into Germany via an empty pickle barrel.

Siew, who was of Jewish descent, would then go to the US in 1905, where he would change his name to William L. Laurence – his last name denoting the street he lived on at the time in Cambridge.

An uprising behind him, which saw his nose smashed in by Cossacks during the First Russian Revolution, Laurence’s new world would be re-built in the revolutionary state of Massachusetts.

First he apparently tried his hand at philosophy at Harvard University and then graduated with a law degree from Boston University, at the second time of asking in 1925. The first time around a cheating scandal meant everybody had to retake the exam, at least according to Laurence, who had by then served in the US Signal Corps during World War One.

His career in journalism got off to a rocky start. Laurence had worked for a very brief time at an undisclosed ‘newspaper job’ in Boston until he got fired in 1914, a year after he became a naturalised US citizen.

“They had given me an assignment in a downpour and I had decided I'd sit it out. Of course that was it. I got fired, and I didn't continue after that,” he told a University of Columbia researcher.

But a chance encounter with Herbert Bayard Swope, the then executive editor of The New York World, and a “virtuoso performance” of the word game Ask Me Another landed Laurence a job at the left-learning outlet in 1926.

“You would work six days a week. You would get there at one in the morning, work until one at night, twelve hours a day, 70 hours a week, and miserable pay,” Laurence described The World’s gruelling working conditions.

The experience led him to help co-found the American Newspaper Guild in 1933, the same year Roosevelt came to power and his New Deal of public works projects for the American people began.

Amid the Great Depression, Laurence took the opportunity to jump ship in 1930 when he was hired as The New York Times’ first science reporter under managing editor, amateur mathematician and science fan Carr Vattel Van Anda.

Until then the outlet had commissioned scientists to write about discoveries in their own field. Most notably Albert Einstein, who soon, like Laurence, would join the ranks of Jewish refugees who had fled mainland Europe, wrote for The Times.

Despite being inspired by the Wright Brothers, Laurence was reluctant at first to purely concentrate on science, worrying that he would spend the rest of his days reporting on “dull” gadgets. He even went back to the World asking for a payrise. Once it was rejected, he set-up shop with The Times.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Nuclear physics was on the ascendancy and soon, in 1932, The University of Cambridge’s James Chadwick would discover the neutron.

But before he could get ahead of himself, Laurence would have to disarm the scientific community, who treated journalists as “freaks of nature”. For this purpose, Laurence developed his own technique.

“You come to a scientific meeting, you see a lot of titles to papers, and they may hide some world-shaking events,” he explained. “The title is very innocuous. You have to go first to some authority and say, ‘Which of these papers would you select for coverage?’ And you wouldn't trust one person because he may have prejudices. You go around to several and before long you have marked certain papers on your program.”

Next, Laurence, who had no scientific training, would present pseudo-technical questions so the the experts wouldn’t disregard him, followed by a lay-mans interpretation of a speech or paper, asking for the scientist’s feedback and guidance in shaping his story.

Once such exchange apparently took place between the upstart New York Times science reporter and a young Oppenheimer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the winter of 1932.

“I gave him a start, and I got a page one in the Times the next day. He never forgot it. I saw him thirteen years later in 1945,” Laurence said.

The Drumbeat of War

By 1939, Adolf Hitler had annexed Austria, stolen parts of Czechoslovakia and made a fool of France and the UK with the infamous Munich Agreement. Appeasement and apathy would soon turn to alarm when the Third Reich rolled into Poland in September. Before the Nazis could besiege Warsaw, the age of the ‘atom smashers’ began.

The winter before two German scientists based in Berlin, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, were able to split uranium atoms into smaller elements by bombarding them with neutrons, while scientists at Columbia University were able to replicate the experiment in January 1939.

The process was dubbed ‘nuclear fission’ after the biological principle of a single entity, such as a cell, dividing into two or more parts.

The US was fairly quick off the mark to form its Uranium Committee (later renamed to the more secretive S-1 Committee) in October 1939 after Einstein warned Roosevelt about the potential weaponisation of uranium-nuclear-fission energy.

“This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable -- though much less certain -- that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed,” he wrote.

“A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory. However, such bombs might very well prove to be too heavy for transportation by air.”

The same month Laurence was sensationally reporting on an “atom smasher” of his own after hearing a speech from Professor Ernest Lawrence, a mentor of Oppenheimer at the University of California. He had successfully created a new type of particle accelerator, a cyclotron, and was now ready to tell the wider scientific community about it.

“Dr. Lawrence pointed out in an interview after his formal report, the time is past when the release of atomic energy and the transmutation of base metals into gold is to be regarded as mere dream impossible of realisation on a practical scale,” New York Times readers of the day learnt.

“The production of gold from base metals on a large scale, thus raising havoc with our present economic systems, and the release of atomic energy, which would enable man to tap the same inexhaustible source of power that keeps the sun and the stars going, are not the only goals expected to be attained with the new man-made Prometheus.”

Laurence’s hints to super-weapons would soon envelope the American psyche. The German war machine had ploughed through Europe by June 1940, culminating in Operation Dynamo, the last-ditch evacuation of more than 338,000 Allied soldiers from Dunkirk.

With the fall of France, it was conceivable that, save for the English Channel, Britain would be next and the fascist aggressors would eventually directly threaten the United States.

Roosevelt, with one eye on his attempted re-election that November and his other on Hitler, picked up the pace of his quiet preparations for war during the summer of 1940. This effort included a new munitions programme, the appointment of a Secretary of War in the shape of Republican pro-interventionist Henry Stimson and the creation of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC).

The group funded and oversaw hundreds of different projects, including the atomic bomb research and the development of radar and sonar. Almost exactly a year later in June 1941 the aforementioned Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was born thanks to Executive Order 8807, with the NDRC now reporting into it.

The bureaucratic move came about because the latter organisation lacked serious heft, partly because its members were unpaid part-timers. The OSRD, meanwhile, with Veneer Bush as its director, had a through line to the President and could therefore expedite its efforts to build scientific weapons of war.

That is exactly what happened when Bush briefed Roosevelt and his Vice President Henry A. Wallace on the state of atomic bomb research in October 1941. Three years after the Uranium Committee was formed, it was now given the green light to move into production mode and work with the Army. The Manhattan Project had begun.

Keeping The City Secret

Everything about Manhattan was massive. It cost $2bn (or $32bn in today’s money) and employed around half a million people, most of which were construction workers. The buildings, the disruptive flight paths and land appropriation really started to give the game away from 1943 onwards.

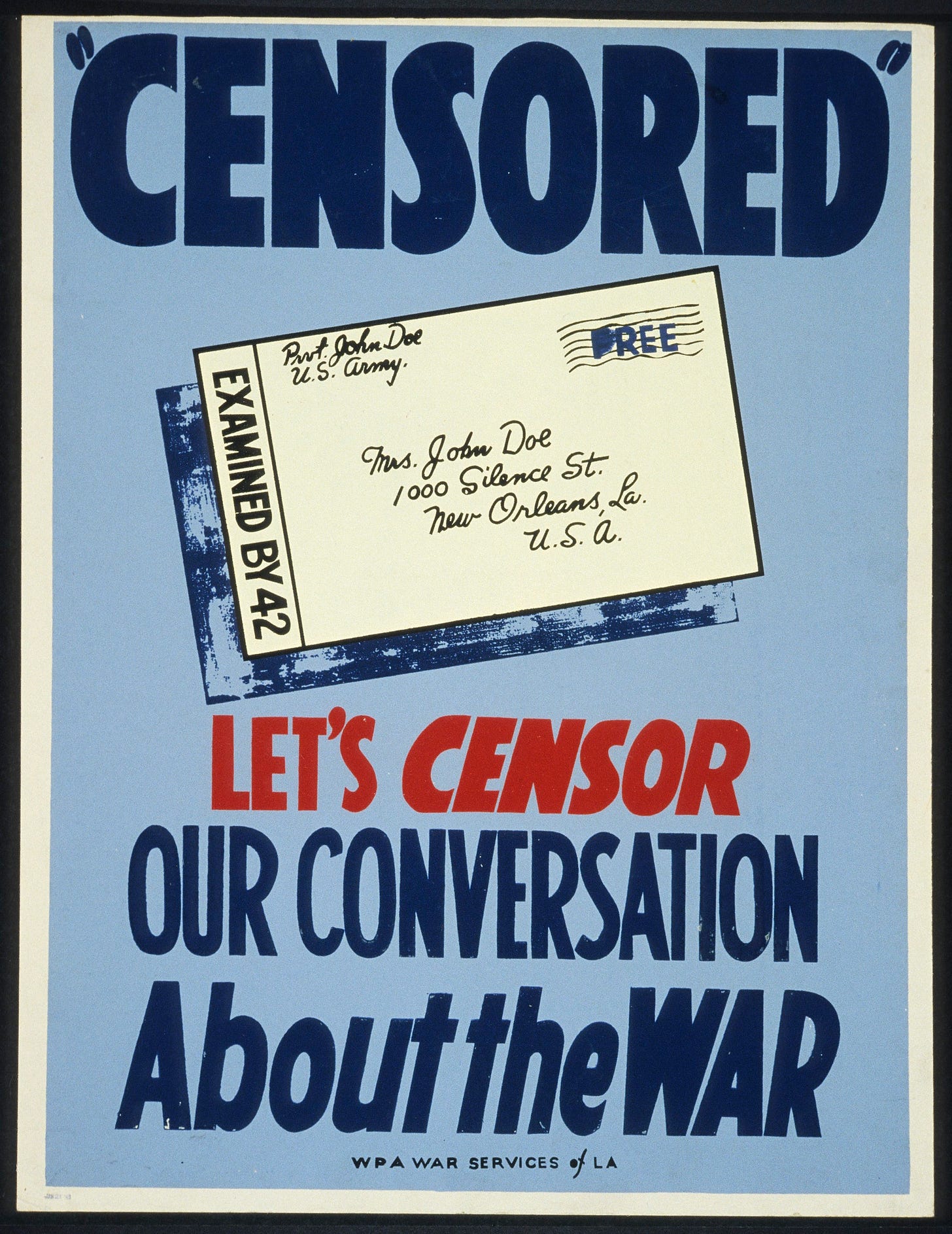

The unenviable task of keeping a lid on the project and out of the papers was given to The Office of Censorship, which was created in the same month the US formally entered the war, December 1941.

Byron Price, an executive news editor at the Associated Press and World War One veteran, quit the wire service and accepted the role as chief censor on the condition that he would report directly to Roosevelt.

Balancing between a fine line of press freedom and keeping America’s secrets away from the prying eyes of the enemy, Price ran a voluntary censorship code – the Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press – and a 24/7 helpline so journalists and editors could run any questions past the censors at any time, given the trade’s unsociable hours.

“To mention freedom and censorship in the same breath might appear a contradiction of terms; for censorship is by its very nature ruthless and arbitrary. It invades privacy and suppresses free enterprise, sacrificing individual interest for national interest without compunction. Yet there is, in reality, no contradiction, and there need be no conflict,” Price wrote in 1942.

Though Price and his team of 13,500 of staff were well-respected by the journalistic community for their thoughtful approach to the situation, the grand scale of the project (Oak Ridge alone had become the fifth largest city in Tennessee at the time) meant leaks were inevitable. It also didn’t help that the Office of Censorship wasn’t briefed about Manhattan until March 1943.

The Oak Ridge Journal, a weekly which initially kept the inhabitants of the secret city up-to-date on the government’s latest propaganda and later focused more on their day-to-day lives, was given the go-ahead in September that year.

“It is hoped that all of you will strive to advance the development of the Clinton Engineer Works and the town of Oak Ridge, in order that the war effort may go on at full place,” the new Tennesseans were told.

Despite the banning of any stories around ‘atom smashing’, ‘atomic energy’, ‘secret military weapons’ or the mention of ‘uranium’, ‘radium’ or ‘deuterium’, Laurence and other journalists still tried their luck.

“One day I got a notice from Price’s office requesting me to refrain from writing or mentioning anything about a certain large number of elements,” he said. In another instance, Laurence tried and tried again to get something published on Germany’s own nuclear efforts, especially after Propaganda Chief Joseph Goebbels made a point to boast about the Nazi’s ‘super weapons’.

He was rebuffed, while others slipped through the net. In total, there were 1,500 leak investigations into secrets escaping from Manhattan. Probably the most egregious was Steel Magazine’s alleged linkage of the code-name ‘Manhattan’ with the atomic bomb project in June 1944.

Before then, The Washington Post had found itself running afoul of the censors in October 1943 by publishing an article which cited an anonymous scientist who had been “studying much of his life on the matter of blowing up nations with an atom”. The New York Post even got in on the act in September 1944 by breaking the voluntary code.

Probably the most bizarre incident was the publication of the science fiction book, The Last Secret, published by Dial Press. Despite being published in 1943 and being a clear violation of the voluntary code – not only did the plot touch upon atom smashing, but super-weapons too – Jack Lockhart, Assistant Director of The Censorship Office, gave Dial Press a mere slap on the wrist by urging caution in the future. A review of the book even appeared in The New York Times in February 1944:

“Keep this under your hat. It's a secret — such a terrible secret that the fate of the world may depend upon it. Alvin Harmon, a physicist, is the discoverer, and he tells Jim Steele about it, only he does not reveal any details. Steele is a member of a very hush-hush Government agency, and he realises at once that Harmon is in very great danger.”

It was clear that by the beginning of 1944, the existence of the Oak Ridge and Washington plants was known by hundreds of journalists and those closest to the scientific community, including Laurence, were continuing to ask awkward questions about forwarding addresses and the lack of physicists at scientific conferences.

Though the secret was half-out, General Groves did praise Price and the Office of Censorship at the end of the war:

"May I express my gratitude to you, the members of your staff, and through you, to all the members of the American press and radio who have been so cooperative in withholding information concerning the atomic bomb project. I would be happy if you could inform the press and radio of my feelings.”

But before any pleasantries were exchanged, the scoop-hungry Laurence was vying for his place in history. The good news was that his battles with the censors, which always ended in defeat, meant that he was top of mind when Lockhart was asked to recommend a press release writer for when the atomic bomb would be tested and eventually used.

At first through a letter to The New York Times’ editorial bosses and then through an in-person introduction, Groves recruited Laurence in the spring of 1945 to work on the secret project.

At 57, Laurence got his affairs in order, temporarily left the Gray Lady and stepped into the unknown. To cover-up his whereabouts, The Times gave him a London by-line.

The Gadget Goes Boom

From Washington, where the headquarters of the Manhattan Project had been since September 1942, Laurence was then moved onto Oak Ridge. He was in a privileged position. Unlike the ORNL workers, the little New York Times man was able to tour the siloed sites and gather a first-hand account of the size and the scale of the project at Oak Ridge.

Though he wrote about the new technological advancements he witnessed, Laurence’s papers were locked away in a safe, while any pieces of scrap paper or notes were burnt. A secret and solitary lifestyle, Laurence at one point stuck to his writing around the clock.

“At the beginning it was very difficult to absorb it all,” he said. “It was also very difficult for me as a newspaperman to see these tremendous developments which should have made huge page one stories, you know, and there I am seeing them and I can’t say a word about it.”

Laurence later visited the nuclear production project in Washington, The Hanford Site, which sat on the banks of the Columbia River. Describing them as “completely staggering”, Laurence explained in Dawn Over Zero that The Hanford piles were the first atomic power plants built on earth and had a “three-in-one” quality about them.

“...Atomic boilers generating enormous amounts of atomic energy in the form of heat. In these boilers atoms by the trillions are ripped asunder and new elements are constantly being created. Many of these, fission products distinct from plutonium, have great potential value in biology, medicine and industry,” he wrote.

From Washington, it was onto New Mexico to the most secretive of sites, Los Alamos. By 1945, ‘Project Y’ had grown to a population of 6,000 people.

Oppenheimer had chosen the site – a former ranch school – himself, helped oversee the building of the facilities and made sure each house had a fireplace and a balcony. He also hoped that the beauty of the nearby Sangre de Cristo Mountains would inspire his fellow scientists.

Though he could say little about the site and there were a sleuth of other military scientific projects ongoing at the time, Oppenheimer was able to convince some of America’s top physicists to join him in Los Alamos, often by Santa Fe. One such scientist was the now world-famous Richard Feynman, who ended up giving Laurence a guided tour of the site in May 1945.

“I remember my amazement when I saw the first real quantity of cubes of uranium-235 piled up, one on top of the other. There was enough uranium there to blow up the whole of New Mexico,” The New York Times reporter said.

Around three months later Laurence would return to New Mexico, but this time 210 miles south of Los Alamos to the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range.

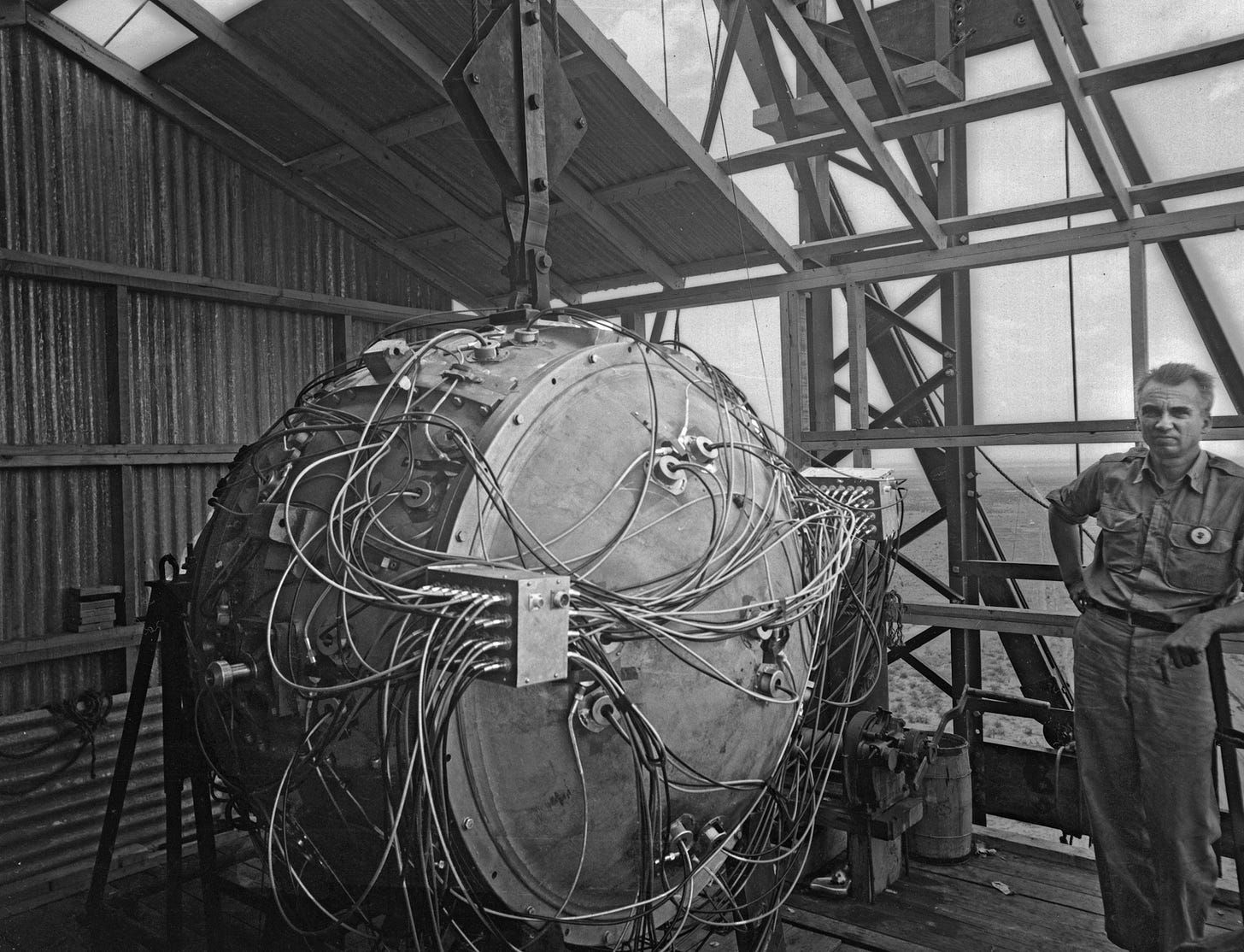

Since spring, Oppenheimer and his team had been making the four-hour drive down to Alamogordo as part of Project Trinity. Then at 5:30 am local time on 16 July 1945 the world entered the nuclear age as ‘The Gadget’, an implosion plutonium device atop of a 150-foot tower, successfully detonated.

Laurence, who had written his own obituary before the test, was around 20 miles from the explosion. Some scientists feared the device could set the world ablaze by igniting the atmosphere, while others thought The Gadget could turn out to be a dud.

Instead, the explosion’s yield was equivalent to 25 kilotons of TNT, with a fireball reaching 660 feet high. The sound wouldn’t reach the observers for at least a minute.

Many of them were lying on the floor in preparation for the blast. “It was as though the earth had opened and the skies had split. One felt as though one were present at that moment of creation when God said, 'Let There Be Light’,” Laurence said of his experience.

Groves put the journalist to good use by helping him write a press release to cover up the real cause of the explosion. An ammunition store of high-explosives was blamed for the blast in a statement partly written by Laurence and issued by the Second Air Force.

Two months later Laurence joined Groves, Oppenheimer and a media pack on a visit to the Trinity Test site. It was a victory lap.

The atomic bomb was no longer a secret after the US levelled the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the start of August, leading to Japan’s surrender on 2 September. Laurence’s double-pay arrangement between The New York Times and the US government saw him write more propaganda in the Pacific.

This included leaflets for the war department and a draft radio address for President Truman to be delivered after the bombing of Hiroshima. It was unsurprisingly scrapped after Groves deemed it to be too sensational.

In line with his then paymasters, Laurence also played down the terrible radiation impacts of the bombs, ‘Fat Man’ and ‘Little Man’, chalking-up the reports of agonising deaths as Japanese propaganda.

These stories, alongside Laurence’s account of the apocalyptic attack on Nagasaki, won him another Pulitzer and were aggregated across the US media landscape, carrying a cleaner and more palatable narrative of the A-bomb with them.

Lord Beaverbrook’s Daily Express, however, was having none of it, publishing an eye-witness account on 5 September from Wilfred Burchett outline the true aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima.

He warned of an ‘atomic plague’. “In this first testing ground of the atomic bomb I have seen the most terrible and frightening desolation in four years of war. It makes a blitzed Pacific island seem like an Eden,” Burchett wrote.

“The damage is far greater than photographs can show…In these hospitals I found people who, when the bomb fell, suffered absolutely no injuries, but now are dying from the uncanny after-effects.

“For no apparent reason their health began to fail. They lost their appetite. Their hair fell out. Bluish spots appeared on their bodies. And the bleeding began from the ears, nose and mouth.”

Laurence, who had returned to The New York Times by the end of August, had already moved on from Japan but not the Manhattan Project.

He spent the rest of the ‘40s writing and reporting on Tennessee, Washington and New Mexico and was eventually promoted to science editor at The Times in 1956. His enemies would call him a fabricator, his allies a patriot – but, above all else, Laurence seemed obsessed with scoops.

“It was a little difficult to come down to earth really. Everything from then on seemed like it might be an anti-climax,” he said of his war adventures.

📖 Essays

How disinformation is forcing a paradigm shift in media theory

Operation Southside: Inside the UK media’s plan to reconcile with Labour

📧 Contact

For high-praise, tips or gripes, please contact the editor at iansilvera@gmail.com or via @ianjsilvera. Follow on LinkedIn here.

FN 156 can be found here

FN 155 can be found here

FN 154 can be found here

FN 153 can be found here

FN 152 can be found here

FN 151 can be found here