How bots invaded social media and changed the world forever

Future News 130

A sordid and long-practised espionage tactic is being reinvented online to catch a new type of foe. Researchers have turned to digital honeytraps in a bid to discover how far automated bots have spread across social media. A lot less sexier than the heart-racing plot of your typical spy movie, the method involves setting up attractive social media accounts and luring and then monitoring other accounts committing malicious behaviour.

The method differs from other detection tactics, including allowing social media users to report bad behaviour and hyperlink monitoring. These systems can be easily gamed as spammers, so-called ‘content polluters’ and influencer-bots become more and more sophisticated by embracing adaptive strategies.

The stakes are massive. Manipulation of social media networks has led to real-world violence, sent the stock market crashing and has allowed terrorist groups to spread their propaganda to millions of people.

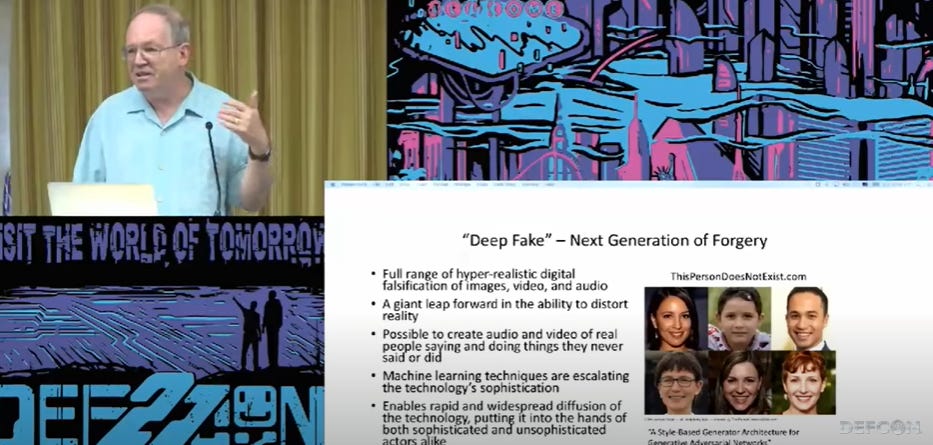

For the US, long engaged in the ‘War on Terror’, social bots became a national security issue worthy of its own investigation when the high risk, high impact Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the US Army held a four-week-long competition into the phenomenon in early 2015 as part of its wider Social Media in Strategic Communication (SMISC) initiative led by Dr Rand Waltzman (pictured below at DEFCON 2019).

Two of the six teams, including representatives from The University of Southern California, Indian University, Georgia Tech University, SentiMetrix, IBM and Boston Fusion, would use honeypot-gleaned data to try and successfully identify 39 pro-vaccination influence bots that they were blind to.

Despite the ‘Trojan Team’ from The University of Southern California achieving 100% accuracy in detecting the influencer bots, social analytics business SentiMetrix came out on top of the competition. It scored 39 out of 40 correct guesses and completed the task six days before the other competitors. Indiana University found all the influencer bots in the same time as Southern California, but made seven wrong guesses.

There was one big technical takeaway for the top three teams from the challenge: machine learning techniques alone were insufficient in hunting down bots because there was a lack of training data for the AI algorithms to test and refine themselves against to begin with.

That meant unsupervised learning, where machine learning programmes are left to find their own patterns, wasn’t an option to start with and the researchers turned to other techniques, including clustering algorithms (the grouping of data points) and online prediction strategies.

“Bot developer are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Over the next few years, we can expect a proliferation of social media influence bots as advertisers, criminals, politicians, nation states, terrorists, and others try to influence populations,” the researchers concluded.

The other major outcome of the project was the coming together of The University of Southern California and University of Indiana teams, a move which was extremely insignificant at the time but could eventually decide the future of Twitter, its 229m users and how we view online discourse and social media companies.

The road to 5%

Bots, spammers and fake accounts have existed since the inception of social media. It was even claimed this year that “bad bots” made up anywhere between 27.7% and 40% of internet traffic. For Twitter, founded in March 2006, it was merely a matter of time before this software-derived nuisance would dog the platform.

One of the business’ earliest acknowledgments of the problem came in 2008 when Twitter co-founder Biz Stone sounded the alarm on spam, announcing a range of counter-measures the platform would introduce. Those included making it easier to suspend accounts, increased user participation in alerting Twitter to spammers and the formation of an anti-spam team.

“It’s unfortunate that this has to be done but we’re going to hire people whose full time job will be the systematic identification and removal of spam on Twitter,” Stone wrote. “These folks will work together with our support team, and our automatic spam tools. Our first ‘spam marshal’ is starting at Twitter next week.”

The issue became very public in 2009 when American baseball coach Tony La Russa sued Twitter after a disparaging account was set-up under his name. At the time, Twitter denied it had settled with La Russa and publicly revealed its blue tick verification system for the first time, which was then in beta mode.

“Please note that this doesn’t mean accounts without a verification seal are fake—the vast majority of Twitter accounts are not impersonators,” Stone stressed. “Another way to determine authenticity is to check the official web site of the person for a link back to their Twitter account.”

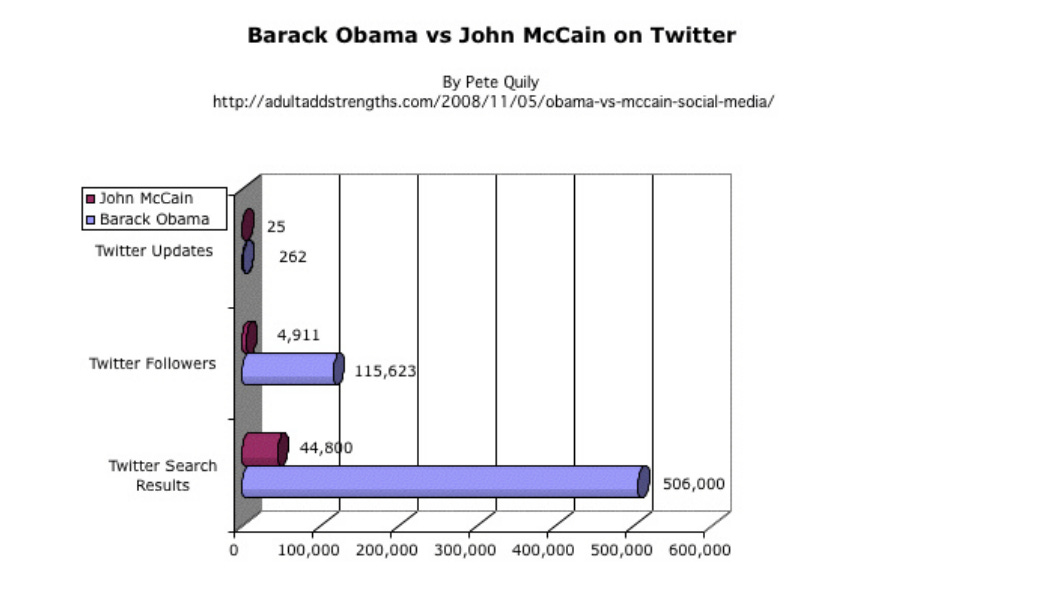

A ‘Report as Spam’ button came later that year as well as a Twitter’s promise to “continually evolve” its tools to help fight spam and bots. In Washington, meanwhile, there was a historic change of guard, with the election of President Barack Obama to the White House. It was the first US Presidential election campaign in the social media era, with Obama having 23 times more followers on Twitter than Republican rival the late John McCain.

The true size of Twitter’s bot problem wouldn’t be revealed until more than a year after Obama’s re-election. As part of the company’s IPO process in 2013, the business filed a S-1 form with regulators the SEC that October.

Serving as a warts and all prospectus for current and potential investors, the good, bad and the ugly financial sides of a business must be disclosed in S-1s. It is under this system that Twitter estimated that false or spam accounts represented less than 5% of the platform’s monthly active users (MAUs).

“However, this estimate is based on an internal review of a sample of accounts and we apply significant judgement in making this determination. As such, our estimation of false or spam accounts may not accurately represent the actual number of such accounts, and the actual number of false or spam accounts could be higher than we have currently estimated,” the company conceded.

The IPO got over the line, with Twitter listing on The New York Stock Exchange rather than the tech-heavy NASDAQ in November that year. It priced its shares at $26 each, rising by more than 73% to $44.90 on the first day of dealings, giving the company a market cap’ of $31bn.

It would be months until trouble began to brew for the company. 2014 saw Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea, with a renewed media and political focus on how the country was manipulating social media networks, as well as a growing realisation that terror groups, most notably ISIS/The Islamic State, were increasingly using social platforms to spread their propaganda (The Brookings Institute claims that at least 46,000 Twitter accounts were used by the jihadists in 2014).

Twitter, meanwhile, was forced to deny reports in August 2014 that up to 8.5% of its MAUs, amounting to 23m accounts at the time, were bots. The company stressed this was down to false media interpretations of an SEC filing, which stated that: “In the three months ended June 30, 2014, approximately 11% of all active users solely used third-party applications to access Twitter.

“However, only up to approximately 8.5% of all active users used third party applications that may have automatically contacted our servers for regular updates without any discernible additional user-initiated action. The calculations of MAUs presented in this Quarterly Report on Form 10-Q may be affected as a result of automated activity.”

The Return of The Geeks

Already three years into its shadowy work, DARPA’s SMISC started advertising for its latest competition in 2014. This was the initiative where The University of Southern California and Indiana University teams would compete and crucially meet at the start of 2015. The researchers said the 8.5% estimation — whether it was an misinterpretation or not — was one of the key motivations behind the study.

“According to a recent Twitter SEC filing, approximately 8.5% of all Twitter users are bots,” they wrote. “While many of these bots have a commercial purpose such as spreading spam, some are ‘influence bots’ – bots whose purpose is to shape opinion on a topic. This poses a clear danger to freedom of expression…”

However, a later and bigger figure would haunt Twitter. In 2017, researchers at The University of Southern California and Indiana University would team-up to launch another investigation into Twitter bots, estimating that between 9% and 15% of accounts on the platform were fake. That would have amounted to 48m accounts at the time.

“To characterise user interactions, we studied social connectivity and information flow between different user groups,” the academics said. “We showed that selection of friends and followers are correlated with accounts bot-likelihood. We also highlighted how bots use different retweet and mention strategies when interacting with humans or other bots.”

The report couldn’t have come at a politically worse time for Twitter. Donald Trump’s surprise election to the White House in late 2016 put an even sharper focus on social media platforms and their role in the public sphere. Obama’s use of the platforms may have been charming and savvy, but Trump’s embrace of social media was worrying and potentially malevolent, so the media narrative went.

It was in this context and amid claims of further Russian meddling with social media that the powerful US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence launched its own investigation. Facing a grilling from the Republican chairman of the committee, Richard Burr, Twitter’s then acting General Counsel Sean Edgett was quizzed on the 15% bot estimate from the University of Southern California and University of Indiana teams. Edgett hit back, repeating the “less than 5%” internal estimate from Twitter, whilst questioning the researchers’ so-called ‘Botometer’ approach.

“While our detection tools for false or spam accounts rely on a number of inputs and variables and do not operate with 100% precision, they are informed by data not available outside of Twitter,” he told the cross-party group of senators.

“Our internal researchers have access to and can analyse a number of different signals including, among other things, email addresses, phone numbers, login history, and other non-public account and activity characteristics that enable us to conduct a more thorough review and reach more accurate conclusions as to whether the account in question is fake or spam.

“We keep such information confidential and do not make it available to researchers in order to protect the privacy of our users. Because third-party researchers do not have access to internal signals that Twitter can access, their bot and spam detection methodologies must be based on public information and often rely on human judgement, rather than on internal signals available to us.”

Published in October 2019, the Committee’s final report concluded that Russia did attempt to interfere in the 2016 US election using social media platforms and a key tactic was to run bots across the networks.

“Russia-backed operatives exploited this automated accounts feature and worked to develop and refine their own bot capabilities for spreading disinformation faster and further across the social media landscape…In January 2018, Twitter disclosed its security personnel assess that over 50,000 automated accounts linked to Russia were tweeting election-related content during the U.S. presidential campaign,” a key line of the 85-page investigation concluded.

Twitter acquired trust and safety tool Smyte in 2018, the Covid-19 pandemic came calling in late 2019, with social media platforms taking proactive and sometimes controversial actions to stop the spread of disinformation and fake news, and Democrat Joe Biden beat Trump in the 2020 US Presidential election. The bot matter now seemed behind Twitter.

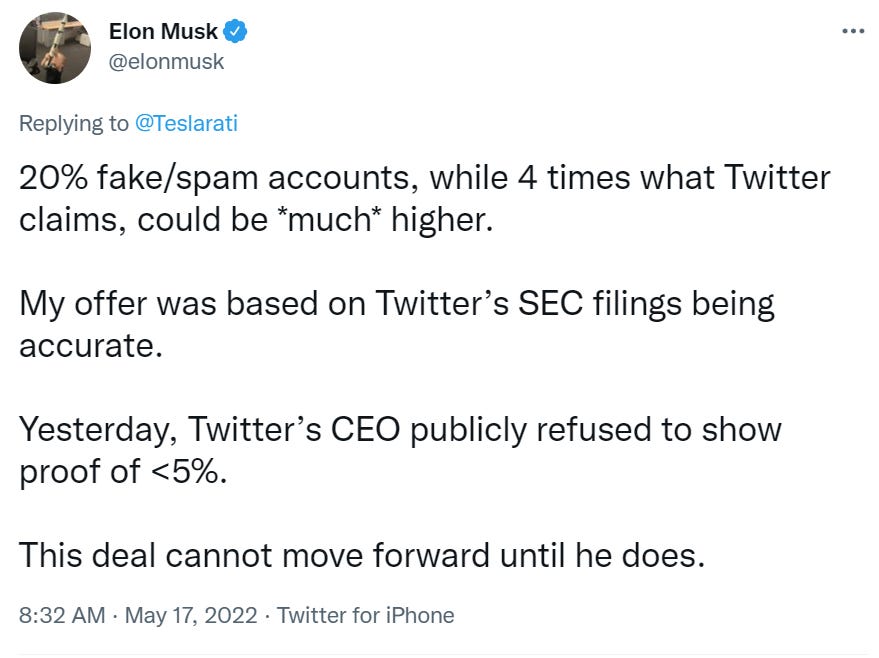

Then along came Elon. Musk’s $43bn all-cash consideration for Twitter in April looked like it would face resistance from Twitter’s board, but they later sided with the Tesla CEO. The whole deal was put into question when Musk claimed, without citing any references, that 20% of all Twitter accounts were fake or spammers.

"My offer was based on Twitter's SEC filings being accurate," Musk said. "Yesterday, Twitter's CEO publicly refused to show proof of <5%. This deal cannot move forward until he does."

Though much has been made of Musk’s true motivations behind the tweet – whether the billionaire was using this as a negotiation tactic to get a better price for the platform or not – it is still unclear how Twitter came to the “less than 5%” figure, an estimation that has been doing the rounds since at least 2013. “Transparency is core to the work we do at Twitter,” the company has declared. Is it now time that Twitter shows its workings?

📺 Media news of interest

YouTube removes more than 9,000 channels relating to Ukraine war

Media gets banned from CPAC, the flagship right-wing conference

📧 Contact

For high-praise, tips or gripes, please contact the editor at iansilvera@gmail.com or via @ianjsilvera. Follow on LinkedIn here.

FN 129 can be found here

FN 128 can be found here

FN 127 can be found here

FN 126 can be found here

FN 125 can be found here