Cheaper, Faster, Easier: Why Deepfakes Are Baffling Lawmakers

The US, UK and EU are trying to catch-up with the AI tech

We’ve had almost seven years to get our heads around deepfakes and their potential impact on society. Fraud, democracy, copyright, porn and everything in between. The first popular synthetic audio-visual hoax made news back in July 2017.

A team of researchers at The University of Washington (funded by Samsung, Google, Facebook and Intel) published their Obama deepfake to the world. It was way before the generative AI boom of March 2023 and when this brand of machine learning was actually described as ‘neural network AI’. How times have changed.

The big development with the technology was that people could use ‘videos in the wild’ moving forward to produce a deepfake, rather than relying on multiple studio sessions to make a successful audio-to-video conversion process. Those tools became more prominent and popular, and now amateurs can create this type of con-job.

Since the late 2020s the US’ Department of Homeland Security, the US Congress as well as the NSA and FBI, have all issued warnings about the technology. Their latest advice is here, and it comes with a big warning:

“Dynamic trends in technology development associated with the creation of synthetic media will continue to drive down the cost and technical barriers in using this technology for malicious purposes.”

In other words, making deepfakes is only going to become cheaper, faster and easier. For good measure the UK government, the EU and several other governmental, non-governmental and private sector bodies have also sounded the alarm on synthetic media.

Yet, here we are in 2024 with stories about deepfake robo-calls and deepfake scams (Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Joe Rogan and Jennifer Lawrence are just some of well-known faces which have been misused).

And we have Taylor Swift reportedly considering a landmark legal battle to take down fake AI pornographic images of her doing the rounds on social media platforms. The situation got so bad that X/Twitter put a temporary ban in place to stop searches of the performer.

But how can these kinds of incidents be stopped for good? Well, here’s the scary bit from the Department of Homeland Security’s report:

“The threat of deepfakes and synthetic media comes not from the technology used to create it, but from people’s natural inclination to believe what they see, and as a result deepfakes and synthetic media do not need to be particularly advanced or believable in order to be effective in spreading mis/disinformation.”

This has left lawmakers across the globe effectively baffled by the technology. Do we begrudgingly accept that there will be a decline in trust with audio-visual content going forward? How, ultimately, should it be legislated against and regulated? Is there anything we can do?

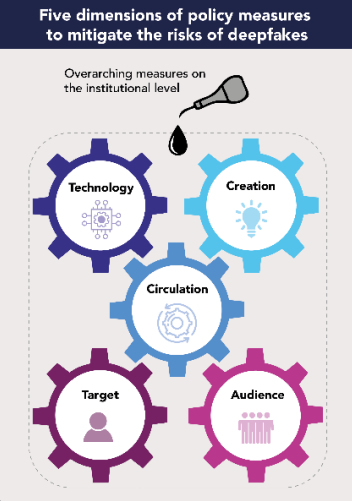

A helpful exercise to break down the problem comes from the EU, which has identified five ‘dimensions’ of deepfakes: the technology, the creation process, circulation, targets and audiences.

The EU approach

Once the EU’s AI Act is passed into law, the 27-nation bloc will seek to regulate the use of synthetic media through transparency obligations placed on creators.

This would fall under Article 52(3) of the proposed Act, which is branded by the EU as the ‘world first comprehensive AI law’ and is expected to come into force later in the year following votes at the EU Parliament level.

“The transparency requirements will include, inter alia, informing users that they are interacting with an AI system and marking synthetic audio, video, text and images content as artificially generated or manipulated for users and in a machine-readable format,” according to lawyers White & Case.

How the EU will regulate such transparency measures is unclear. Malicious deepfakes, much like online fraud and hacking, are a global phenomenon and they could be easily created outside of the EU’s jurisdiction and then circulated to its citizens.

The proposed legislation does not seem to take into consideration the other ‘dimensions’ of deepfakes, namely the technology, targets or audiences. And shouldn’t social media companies also be doing more to combat this problem? The EU’s ‘comprehensive’ legislation looks limited.

There are also valid concerns around free speech. If a satirist makes a deepfake of a politician, should that be taken down if it’s not clearly marked as AI-generated content? And then there’s the simple question of resources - how will the EU actually enforce these new rules and what kind of manpower will they or their member states put behind it?

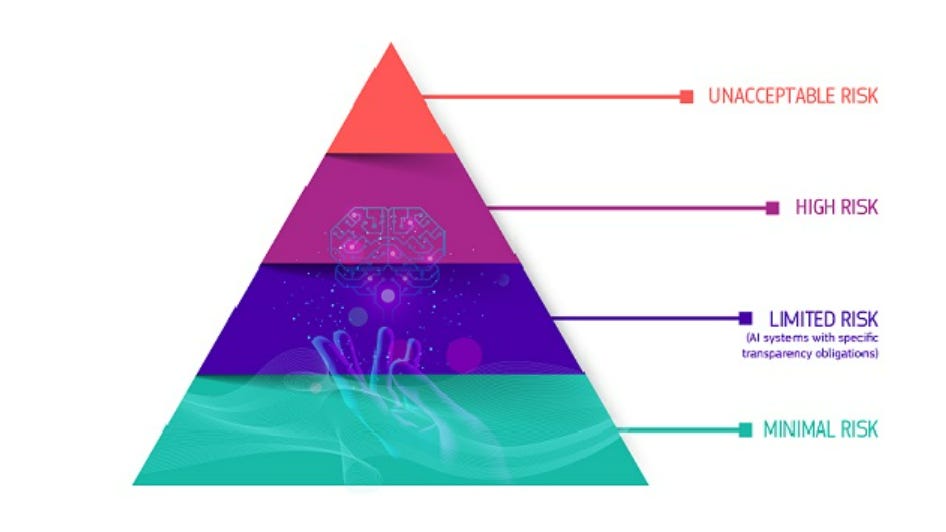

The EU Commission has currently categorised deepfakes as a ‘limited risk’ technology, the the second lowest ranking in the EU AI Act’s risk hierarchy behind ‘unacceptable risk’ and ‘high risk’ but above ‘minimal risk’. Synthetic media is not a top priority, despite EU citizens’ apparent anxieties around the technology.

The UK approach

Describing itself as ‘pro-innovation’, the UK government is taking a notably different approach to the EU. Rishi Sunak’s administration is seeking to regulate AI through existing watchdogs (OfCom, the FCA and so on), rather than attempting to put a ‘comprehensive’ piece of legislation on the statute books.

The government ultimately wants to be flexible as AI technology rapidly evolves. But there are some specific pieces of UK law which address deepfakes. The Online Safety Act, which came into force in October 2023, criminalises people who share explicit and non-consensual deepfakes.

Other pieces of legislation need to be updated, namely the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. As it stands, performers have “rights to consent to the making of a recording of a performance and to make copies of recordings”.

But modern-day deepfake technology doesn’t need new recordings, it uses a combination of old recordings. Therefore no consent is needed. This is plainly unfair.

One proposal to deal with the evolving issue, which spans way beyond the creative sectors, is that the UK government should introduce new rights to protect against the unauthorised use of a person’s face and voice by AI.

But the enshrinement and enforcement of such rights could create another problem, namely the roll-out of digital IDs and the creation of a massive government database full of personal information. The state would be significantly expanded and personal privacy would be eroded.

Here’s what human rights organisation Liberty had to say on the matter back in 2020:

“The Government has given us plenty of reasons to be wary of its digital projects. Recent months have seen backtracks over the planned contract tracing app and exams algorithm, and only last year the Home Office had to apologise to EU nationals and Windrush citizens in the space of a week for data breaches.

“National digital ID systems tend to rely on creating huge central databases, meaning all of our interactions with the State and public services can be recorded. This personal data could then be accessed by a range of Government agencies or even private corporations, potentially in combination with other surveillance technologies like facial recognition.”

Elsewhere, with local and regional elections planned for May and a general election expected later in the year, the UK government is also attempting to fend off foreign adversaries who could seek to undermine the country’s democratic process by using deepfakes.

It’s a very real threat. Just last year a deepfake audio of Mayor of London Sadiq Khan calling for Remembrance Day to be postponed was shared across social media.

The Metropolitan Police decided the creation of the synthetic media wasn’t a criminal offence. It was a classic disinformation play, with the perpetrators using a ‘wedge issue’ of military remembrance to stir things up.

The incident came months after the UK government established the Defending Democracy Taskforce (DDT) under the oversight of Security Minister Tom Tugendhat.

It’s unclear what exactly the DDT does and how it’s resourced, but Tugendhat has revealed that its mission statement is to “reduce the risk of foreign interference to the UK’s democratic processes, institutions, and society, and ensure that these are secure and resilient to threats of foreign interference”.

Established in November 2022, the DDT is cross-departmental, including the Cabinet Office and Home Office, and inter-agency, working with law enforcement and the UK Intelligence community.

“That taskforce will engage closely, both nationally, with Parliament and other groups and stakeholders, and internationally, to learn from allies who are also facing elections over the same period,” Tugendhat added.

So far the DDT has met at least 11 times over the 12 months to January 2024. But members of the House of Lords, namely Labour’s Viscount Stansgate (Stephen Benn), have called for more transparency around the organisation, something which the minister for AI Viscount Camrose (Jonathan Berry) has promised.

The US approach

Lawmakers across the Atlantic are also scrambling to address the deepfake conundrum. After floating several bills around the issue, including the NO AI FRAUD Act and the NO FAKES Act, a cross-party consensus seems to be forming around the Disrupt Explicit Forged Images and Non-Consensual Edits Act, otherwise known as the DEFIANCE Act, in the US Senate.

The bipartisan bill is designed to criminalise those who are responsible for the proliferation of non-consensual, sexually-explicit deepfakes. “The laws have not kept up with the spread of this abusive content,” its backers have warned.

And since the draft legislation is being sponsored by the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee, whose members include GOP heavyweight Lindsey Graham and Democratic Party powerbroker Dick Durbin, it has a good chance of being voted into law.

There is, however, lots of ‘politics’ to be negotiated before then and as it stands no federal legislation currently exists to combat deepfakes. In some cases, deepfake creators could also be protected by the First Amendment.

At a state level, the likes of Texas and California have passed laws banning the use of deepfakes to influence elections. And 10 states have legislated against deepfake porn.

The end of trust

It’s progress, but the wider global picture is depressing. Lawmakers look at least a step behind the technology and the malicious actors exploiting it.

Businesses are equally unprepared, with almost 50% of company leaders telling KPMG that they have no plans/have not taken steps to counter the deepfake threat.

So what’s the way forward? If you boil the issue down to one overriding factor. it’s trust. The adoption of zero-trust cyber-security architectures, where humans and non-humans have to constantly verify themselves (eliminating implicit trust), directly addresses this problem.

But to avoid privacy and security issues (government-backed digital IDs and massive, centralised databases) when implementing such a system, a decentralised or peer-to-peer approach seems to be the most attractive.

Eventually, you land on blockchain technology (or something similar) and its immutable ledgers as a potential solution to the deepfake problem.

🎥 Video essays

📖 Essays

How disinformation is forcing a paradigm shift in media theory

Welcome to the age of electronic cottages and information elites

Operation Southside: Inside the UK media’s plan to reconcile with Labour

📧 Contact

For high-praise, tips or gripes, please contact the editor at iansilvera@gmail.com or via @ianjsilvera. Follow on LinkedIn here.

173 can be found here

172 can be found here

171 can be found here

170 can be found here

169 can be found here

168 can be found here