What Is The ‘Manosphere’ Anyway?

Why self-help gurus are thriving on YouTube and TikTok

"Perfected cocoa for health and strength," exclaimed a series of advertisements in The Times of London during the early 20th Century. They were the work of Friedrich Wilhelm Müller, otherwise known as Eugen Sandow.

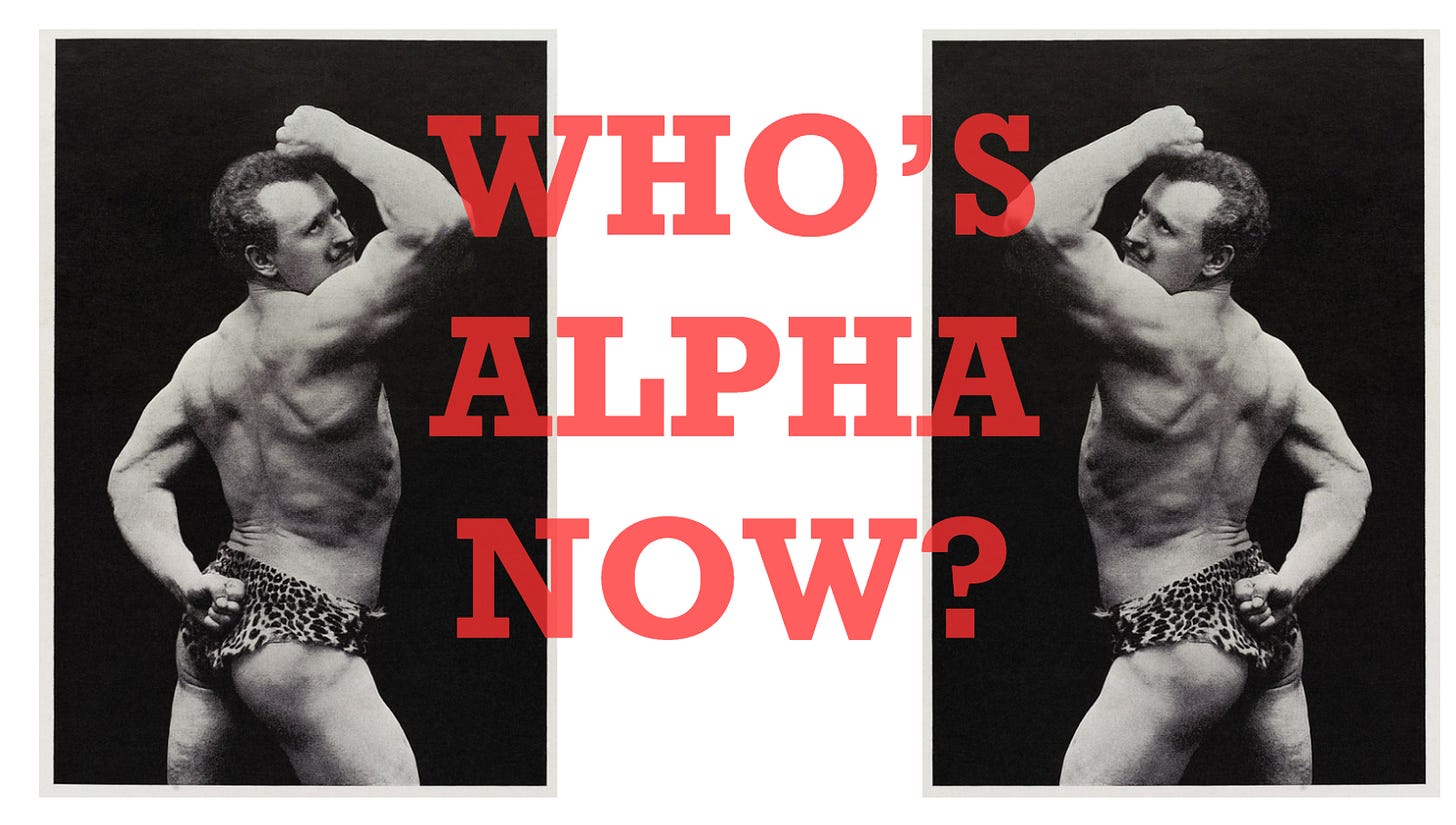

The Prussian showman is now regarded as the father of modern bodybuilding. But Sandow’s legend really started when he first came to London in 1889 to show-off his physical prowess.

The Victorians were increasingly fascinated by fitness, with Sandow competing in carnivals and shows up and down the country. And advancements in photography also boosted his popularity as souvenir snaps of the Herculean Sandow caught-on.

His new-found celebrity led him to design exercises for the British Army in between the Boer Wars and Sandow also hosted a bodybuilding contest at the iconic Albert Hall, where one of the judges was none other than Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle.

By then Sandow had published his System of Physical Training (1894) and Strength and How to Obtain it (1897) guides, helping cement his status as the world’s learning fitness guru.

A serial entrepreneur, Sandow later launched a ‘Curative Institute’ in 1907. A stone’s throw from Buckingham Palace, the organisation boldly claimed to “cure illness without medicine” by using exercise and diet.

Even the ageing process could be prevented, according to Sandow. “There is no other way in which youth may be so surely and pleasantly maintained or renewed,” one of his advertisements pronounced.

Not stopping there, Sandow released his own diet drink through the Coca and Chocolate Limited company in 1911. The supplement was heavily marketed as a “health and strength” enhancer.

But much like his other products and services, the actual science to back-up Sandow’s claims were non-existent. He instead relied on endorsements and appeals to authority – sometimes his own.

The grandest endorsement came in 1911 when King George V titled him as a Professor of Scientific and Physical Culture. Though the role was strictly ceremonial, the royal recommendation meant Sandow’s status had reached new heights.

That would soon come to an end. With England and its Empire pitted against Germany in the Great War, Sandow’s background and accent put him at odds with the public. The Sandow Cocoa Company went bust in 1916.

A lifelong fitness fanatic, Sandow would die in his 50s. His legacy, including the good, the bad and the mad of his influencing ways, is still felt today.

The Supplement Game

Enter the self-styled ‘Liver King’, a muscled American social media influencer who promotes eating raw offal and following “ancestral tenants” to become just as jacked as he is.

Like Sandow, Liver King has another name: Brian Johnson. And that isn’t the only thing these bodybuilders have in common.

Johnson has been involved in his own supplement brand, Heart & Soil, which promises to “reinforce your manhood” or “spark your weight loss” by consuming dried animal organs.

It was all going well for the Liver King. Tens of millions of views across Instagram, TikTok and YouTube as well as high-profile podcast interviews, that was until he was exposed for steroid use in 2022.

The investigation didn’t come from the established media, instead a popular fitness channel called ‘MorePlatesMoreDates’ published an hour-long video on the subject, methodically examining Johnson’s claims (link).

“Back then he was already getting criticism for claiming natural…Since then he’s been able to get more jacked, despite being in his mid-40s, travelling constantly and having more on his plate than ever from an entrepreneurship perspective,” host Derek Munro explained.

He would later reveal in the video that Johnson had reached out to a bodybuilding coach asking for assistance to maintain and build his physique. The email exchange included admissions of Johnson’s ‘stack’ – his collection of performance enhancing medicines.

Liver King later admitted to “lying” and “misleading lots of people” (link), while Munro was widely praised for exposing him. The case was also an example of the so-called “manosphere” policing itself. But what the hell is the “manosphere” anyway?

Again, Munro can help us understand it. Although the term is often used broadly and sometimes inaccurately, the “manosphere” of today has its roots in the pick-up artist (PUA) culture of the 2000s.

At least two books stick out from that period, Neil Strauss’ The Game: Undercover in the Secret Society of Pickup Artists (2005) and The Mystery Method: How to Get Beautiful Women Into Bed (2007).

These types of guides were marketed as providing shy men with a framework to approach women. It all sounds innocent enough.

But critics accused them and the wider PUA community, which often interacted across internet forums, of promoting coercive and manipulative tactics. Negging, where someone makes a backhanded remark in a bid to deflate a target’s confidence, is one such example.

Munro was candid about his own experience of the PUA literature, stating that “99% of the techniques” didn’t work in the real world (link). Instead, he encouraged young men to build up their own self-confidence.

“Get in shape, get a good workout and max yourself in a social standing aspect,” Munro declared.

Internet Culture

Though they were a product of the pre-Broadband Age, some sections of the PUA community thrived on the internet and they took their language with them. Phrases like “alphas” and “betas”, denoting a man’s prestige, soon became popular.

The advent of Web 2.0 in the 2010s and the rise of social media platforms, including YouTube and Facebook, also brought some PUA behaviour into the mainstream.

You also had a crosspollination of communities online, with gamers, influencers, PUA-types and incels mixing and promoting anti-feminist tropes.

Users on infamous forums like 8Chan egged each other on to post more outrageous and bizarre content, normalising behaviours which would have been deemed degenerate in the offline world.

These trends coincided with the rise of smart devices, which, as we know now, have established ‘solo-viewership’. The end result is that family members or friends aren’t able to challenge lies, misinformation or untruths as they are consumed.

And as trust in established media continued to fall in the latter half of the 2010s and social media consumption continued to grow, the ‘Red Pill’ movement began to grow.

Based on the metaphorical choices presented to Neo in The Matrix (1999), the Red Pillers promise to enlighten viewers, sometimes with unsettling consequences (link).

Though initially consigned to the issues of gender roles and identity, the Red Pillers spread their message to the world of politics, promoting an anti-establishment worldview where ‘elites’ are trying to undermine individual liberty and sometimes even cover-up heinous crimes.

The archetypal Red Pillar over the past few years has been Andrew Tate, the self-proclaimed misogynist who used his coaching platform to make his videos go viral on TikTok and gain worldwide fame.

Tate had tried to gain fame before. First through Channel 4’s Ultimate Traveller (2010) show and then on Big Brother in 2016, where he was kicked off the show by producers.

It’s easy to point to Tate and describe him as the pin-up for the “manosphere”, but another ex-reality TV contest provides a good example of why the phrase isn’t as clear cut as some people would have you believe.

Chris Williamson (link), who appeared on Love Island in 2015, has built a hugely popular media business thanks to his long-form interviews with academics, commentators and journalists often about male-related issues.

The scorecard of guests is definitely to the right and you won’t be surprised to hear that he’s interviewed Jordan Peterson, Dominic Cummings and Dan Bilzerian. But there are detractors in there too, including Helen Lewis, Rory Stewart and Johann Hari.

You can hardly call him extremist, but surely he’s part of the “manosphere”? Likewise, Williamson’s house-mate, Zack Telander, is another good example. Here’s an internet personality who played a part in Liver King’s downfall and mostly posts about Olympic weightlifting, rather than politics, culture or society.

Is Telander part of the “manosphere”, even if he’s improving your fitness and wellbeing? It’s worth considering the question because both the FT (link) and Bloomberg (link) have run separate features on the “manosphere” recently, specifically looking at a network of personalities with some connections to Joe Rogan.

Though both stories do make the important point that shows like Lex Fridman and Theo Von mostly have non-politicians on, they failed to fully explain that Donald Trump had been building relationships with popular podcasters for the past three years.

Likewise, Rogan himself had been a long-term Bernie Sanders supporter (link) and there’s a strong argument to be made that Andrew Schulz and Logan Paul have aligned themselves with the most popular causes in a bid to attract eyeballs, while not displaying much ideological convictions themselves.

But this, of course, would make the narrative a bit messier. And probably the strongest charge against the “manosphere” podcasters hasn’t been levelled yet. There is a propensity to have a guest on who agrees with the host’s own worldview or worse – the host is incapable of challenging their claims.

A point in case would be Fridman’s interview with technology investor and creator Marc Andreessen (link), who endorsed Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges’s The Ancient City (1864), claiming that “nothing has changed…he had the exact same access to the [classical] materials we have access to…we’ve learned nothing”.

Prima facie this statement sounds plausible until you realise the history-building Oxyrhynchus Papyri project didn’t even start until 1898, some three decades after Denis Fustel de Coulanges’s conservative book. I’ve written about it in the past (link):

“Archaeologists and classicists have been excavating and deciphering bits of papyrus paper and animal skin parchments from a site south-southwest of Cairo since the late 19th Century.

“The 500,000 fragments of literary, cultural, legal, scientific, administrative, religious and political documents at Oxyrhynchus go as far back as the last dynasty of ancient Egypt,

“The Ptolemaic Kingdom (established in 305 BC), and run through to the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the 7th Century AD.

“The texts are written in Greek, ancient Egyptian, Coptic, Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, and Pahlavi, making the already mammoth task of putting together and translating the scraps of information even more difficult.”

It may be easy to accuse me of pedantry here, but the point is that these long-form interview podcasts often go awry when the host is over their skis on the subject matter. Fridman’s academic background is in science and not the classics, therefore he didn’t know how wrong Andreessen was. Rogan is guilty of this too.

So perhaps this is the strongest charge against the “manosphere”? Like Eugen Sandow, it’s not necessarily mendacious, just a little ignorant.

The Political Press Box

Find my latest long-form audio interviews of political communicators here. Please like, subscribe and listen.

📧 Contact

For high-praise, tips or gripes, please contact the editor at iansilvera@gmail.com or via BlueSky (link). Follow on LinkedIn here.

214 can be found here

213 can be found here

212 can be found here

211 can be found here

210 can be found here