Trump, The JFK Files and The 'Wilson Plot' (Part One)

Can the incoming President help solve a very British mystery?

For journalists and academics who cover the secret world in the UK, it’s long been known that the US system is far more open than the British state and its archives have subsequently proven to bear more fruits.

America has stronger freedom of information rules and the country’s culture (see my essay on the First Amendment here) lends to a more transparent approach. But any nation faces natural limits on the information it can disclose publicly. That is until something extraordinary happens.

It took thirty years, but after the passing of the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992 the US government began to release troves of hitherto secret CIA and FBI files into the world.

Five million pages of records have been released (link), but there are still thousands of files which have been withheld. President Trump has promised to release these to the public.

This series explores how those files could help solve a mystery which still alludes historians and journalists today: was there really a ‘plot’ inside the Security Service, which was then working outside of a statutory remit, to bring down an elected British Prime Minister?

The CIA had a theory. By influencing, infiltrating and inciting the left-wing of the British Labour Party, the Soviets could destabilise the nascent Western alliance and land a major blow in the early stages of the Cold War.

That was the thinking inside the US intelligence community during Dwight D. Eisenhower’s administration, starting in 1953 and ending in 1961. The theory would also play a role in how some of Britain's leading spooks contextualised the brutal assassination of Eisenhower’s successor, John F Kennedy, in November 1963.

At the heart of the CIA’s hypothesis were two main issues: West Germany’s proposed post-World War Two rearmament and the rise of the Bevanites within the Labour Party, a faction which was born when Aneurin Bevan resigned from government in April 1951.

The Welshman was highly critical of pursuing high-levels of military expenditure, while the universalism of the UK’s new welfare state was undermined through the introduction of dental and spectacle prescriptions.

“The Budget was hailed with pleasure in the City. It was a remarkable Budget. It united the City, satisfied the Opposition and disunited the Labour Party—all this because we have allowed ourselves to be dragged too far behind the wheels of American diplomacy,” he bemoaned in the House of Commons.

By October of 1951, the British electorate had had enough of Labour’s in-fighting and serious questions were surrounding the government’s economic competence. Winston Churchill’s Conservatives were subsequently awarded a slim majority in the House of Commons, with Labour failing to gain power again until 1964.

The party’s 13 years in opposition started just after the Cold War really kicked off. The Korean War was raging, Klaus Fuchs, the Soviet atomic spy had been arrested, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were sentenced to death for handing over US secrets to Moscow and Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean had defected to the Soviet Union, while Kim Philby resigned from MI6.

Meanwhile, The Federal Republic of Germany, under its first Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, was still in its infancy and Berlin had become a city of black markets and secret dealings, with spies, sources and refugee groups on both sides of the Cold War seeking to outdo each other in what one senior CIA intelligence officer described as the “information jungle”.

The issue of Germany sovereignty came to a head in March 1952 when Stalin proposed that the country be unified as a neutral entity. It’s still debated by historians to this day whether the Soviet leader’s offer was sincere, but we do know that the US, France and Britain rejected the proposal and called for free elections across the whole of Germany.

The Soviets were given another setback in the summer of 1952 when the foreign ministers of France, West Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, Italy and The Netherlands signed the treaty establishing the European Defence Community. The idea was that the six nations could act as a unified bloc within the wider NATO framework.

The plan was ultimately thwarted by the French Assembly, with West Germany eventually gaining accession to NATO thanks to the London and Paris Conference held in September and October 1954.

By then Stalin had died and The Korean War had ended, but the Cold War had continued. Georgy Malenkov, arguably the true successor to Stalin, had been ousted by Nikita Khrushchev, but he was able to keep the title of Premier of the Soviet Union until February (he was fully thrown to the side-lines in 1955).

It was in this context that Clement Attlee and Bevan travelled to Moscow in August 1954 on their way to Communist China. Their delegation stayed longer than planned, with Attlee resigned to the British embassy while Bevan was given the five-star treatment by the Soviets (see The New York Times here) and a private talk with Malenkov (see The Times here).

Khrushchev also apparently toasted Bevan, rather than Attlee, during a dinner at the British Embassy, a claim which the CIA seized up in a September 1954 report. Just over a year later, however, Bevan’s political career stalled when right-winger Hugh Gaitskell beat him to become Labour Party leader.

He agreed to serve as Shadow Foreign Secretary under Gaitskell and later died in office in 1960 as Deputy Leader. Unfortunately for Labour’s next Prime Minister, the CIA theory about Soviet interest in the party didn’t die with Bevan.

If anything, it intensified and the focus in some quarters would eventually turn to one of the two other ministers who resigned from Attlee’s government in 1951.

His name was Harold Wilson, but MI5 called him ‘Norman John Worthington’ and opened a file on the ex-Civil Service man after he became an MP in 1945, aged just 29, and was soon appointed as a parliamentary secretary at the Ministry of Works.

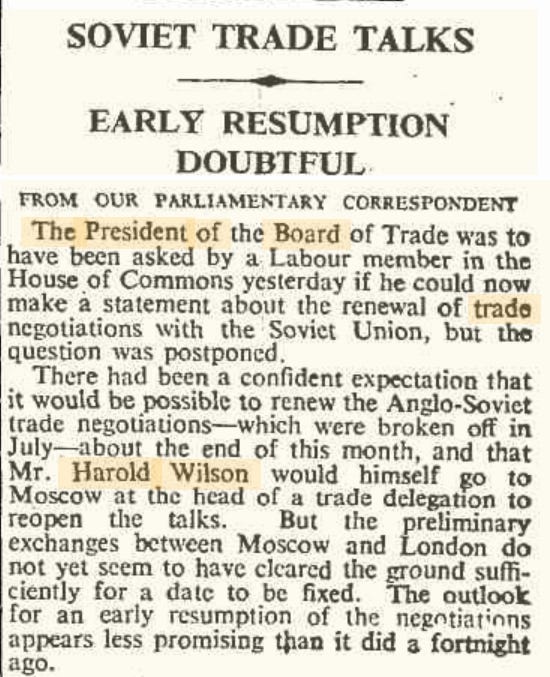

An Oxford Don, a fact which was often played down to pump-up his ‘down-to-earth Yorkshireman’ persona, Wilson’s star rose quickly. He was promoted into Attlee’s Cabinet as the President of the Board of Trade in 1947, making him the youngest Cabinet Minister since 1806.

But it was his trips to the Soviet Union, his dealings with import companies and the associates and advisers he kept during the early stages of the Cold War which really raised eyebrows in intelligence circles.

Next up: ‘The Fundamentalists’

🎙️ The Political Press Box

Find my latest long-form audio interviews here.

📧 Contact

For high-praise, tips or gripes, please contact the editor at iansilvera@gmail.com or via @ianjsilvera. Follow on LinkedIn here.

208 can be found here

207 can be found here

206 can be found here

205 can be found here

204 can be found here

203 can be found here